Carbon Neutral

Share

Carbon offsets are surrounded by a lot of confusion right now. In the ongoing experiment to combat climate change, carbon offsets have gained popularity and controversy alike.

But what are carbon offsets, really? How do they work, and how do we know they’re effective? This article will walk you through Comfy Morning’s offset strategy and how we selected our carbon offset projects.

Carbon offsets explained

Imagine making a mess, let’s say spilling a can of paint. But you don’t know how to clean up paint, or you just don’t want to. So instead of cleaning it yourself, you pay someone to clean up a different can of spilled paint somewhere else, or to prevent another paint can from being spilled. The paint you spilled is still there. But the number of total paint cans spilled in the world is the same as before you spilled yours. This is what carbon offsets are like for the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions we release into the atmosphere.

The good news is that this is a crude analogy. In the paint can scenario, you’d still be side-stepping spilled paint and would never see the benefit of your remote cleaning. Pulling carbon from the atmosphere, however, is different, because it’s beneficial to the entire planet, regardless of where in the world it happens.

People, businesses, and governments can calculate how much carbon they’ve emitted from things like daily life and business operations and then pay to capture or prevent emissions for that amount of CO2. Offsets are sold per metric ton of CO2, and the price range is massive, from a few dollars per metric ton to hundreds of dollars. It all depends on the size of the offset project, the technology used, and the country where it’s implemented.

Offsets are not a perfect solution—but they’re a necessary tool.

You’ve likely heard criticisms of offsets, like:

- “They only absolve people of their guilt and don’t actually curb emission-causing behavior.”

- “It’s hard to validate and quantify the impact of a carbon offset.”

- “There are ‘bad actors’ who exploit the system, creating more greenhouse gas emissions than they otherwise would have, just to make money from curbing them.”

- “There are a wide range of prices for various carbon offsets but many of them are very expensive (making them an unrealistic option) or very cheap (and can they really be doing good for such a low price?).”

Offsets are not a perfect solution—but they’re a necessary tool, especially until we develop better technology to mitigate emissions.

Why Comfy Morning purchases carbon offsets

Comfy Morning has adopted carbon offsets as a tactic that is part of a larger strategy:

- Reduce direct emissions as much as possible.

- Offset all remaining emissions.

To be clear, offsets are not a replacement for taking actions to reduce our carbon footprint—they are a last resort to compensate for emissions we can’t currently avoid.

How did we choose our carbon offset provider?

There are so many different types of carbon offsets out there, using all kinds of different methods and technologies. It’s overwhelming. Offsets can include projects that store carbon in long-term reservoirs, like trees, soil, or wetlands. They can involve projects that reduce emissions from places like landfills, farms, or manufacturing plants. And they can be projects so obscure that it’s hard to make sense of them at all.

We knew we needed to work with a company that satisfied a bunch of our goals, but first and foremost, we knew they needed to take a few key principles into consideration:

- Additionality: The carbon offset needs to lead to a reduction of CO2 emissions that would not have happened otherwise. That means no investments in national parks that are already protected, for example.

- Permanence: This can’t be a short-term solution. Carbon captured and represented in offsets needs to be stored forever, or for a very, very long time.

- No double-counting: Offsets are a one-and-done thing. Their impact cannot be recorded twice.

- Monitoring and verification: Good offsets need to actually do the thing they are meant to be doing, and that thing needs to be able to be verified.

- Scalability: We wanted to invest in projects that have the ability to scale and receive results quickly, without relying on manual processes that take up a lot of time and resources.

Beyond these criteria, though, we wanted a solution that would align with the mission of our company. We believe that problems can be solved using technology, that entrepreneurship is one of the greatest forms of self-expression, and that there is no better person to run a company than someone truly passionate about what they do. These sound like platitudes; they’re not.

Our team used this lens to evaluate many different companies doing good work. We’re still looking at a lot of them, but in the end, Comfy Morning chose Pachama to purchase carbon offsets.

We wanted a solution that would align with the mission of our company.

We did so for many reasons, the most important of which was the way they use technology to do offsetting differently, maximizing the amount of money actually being delivered to their offset projects.

There were some factors that could be considered red flags—Pachama is a team of 10, and they’re a startup. Plus, they’re our sole offset provider for Offset and Shop right now, and many would wisely counsel us to diversify our offsets (stay tuned…). But Pachama stood out to us as an entrepreneurial, technology-driven company. The fact that their team is small means that it’s agile and that each and every person is on its team for a reason.

The Pachama story

Pachama’s CEO Diego Saez-Gil was born in northern Argentina, at the base of the Amazon rainforest. He grew up surrounded by trees and mountains. After graduating from university, he moved to the US and decided to become an entrepreneur.

He launched two companies. The first was a hostel-booking app—a tool he wished he’d had while backpacking himself and which he eventually sold to Flight Centre. Next was Bluesmart, which produced GPS-trackable suitcases, an idea he came up with after he lost luggage full of gifts for family and friends.

When Samsung’s phone explosions led to restrictions of lithium ion batteries on planes, Diego’s battery-powered suitcases were restricted from flying. It was a rough time, but he sold the company’s IP to Travelpro and decided it was time for a new challenge.

Pachama is a short-form of Pachamama, the goddess of the Earth.

Diego took a sabbatical and ended up on a road trip with his two brothers, driving through the rainforest from his home of Argentina all the way up to Peru. The Amazon was incredible, he says, but it was heartbreaking to see the deforestation happening on its borders. Entire ecosystems were disappearing from the world. And that’s when he decided on his next project.

Research told him that standing forests breathe in and contain 30% of all annual human CO2 emissions—and yet we’re cutting trees down. Because of his experience in technology companies, he decided to use tech to help solve this problem.

Diego chose the name Pachama as a short-form of Pachamama, the goddess of the Earth worshipped by the indigenous peoples of Argentina. These people believe the Earth is alive and that we need to honor and protect it.

How Pachama uses tech to maximize offsets

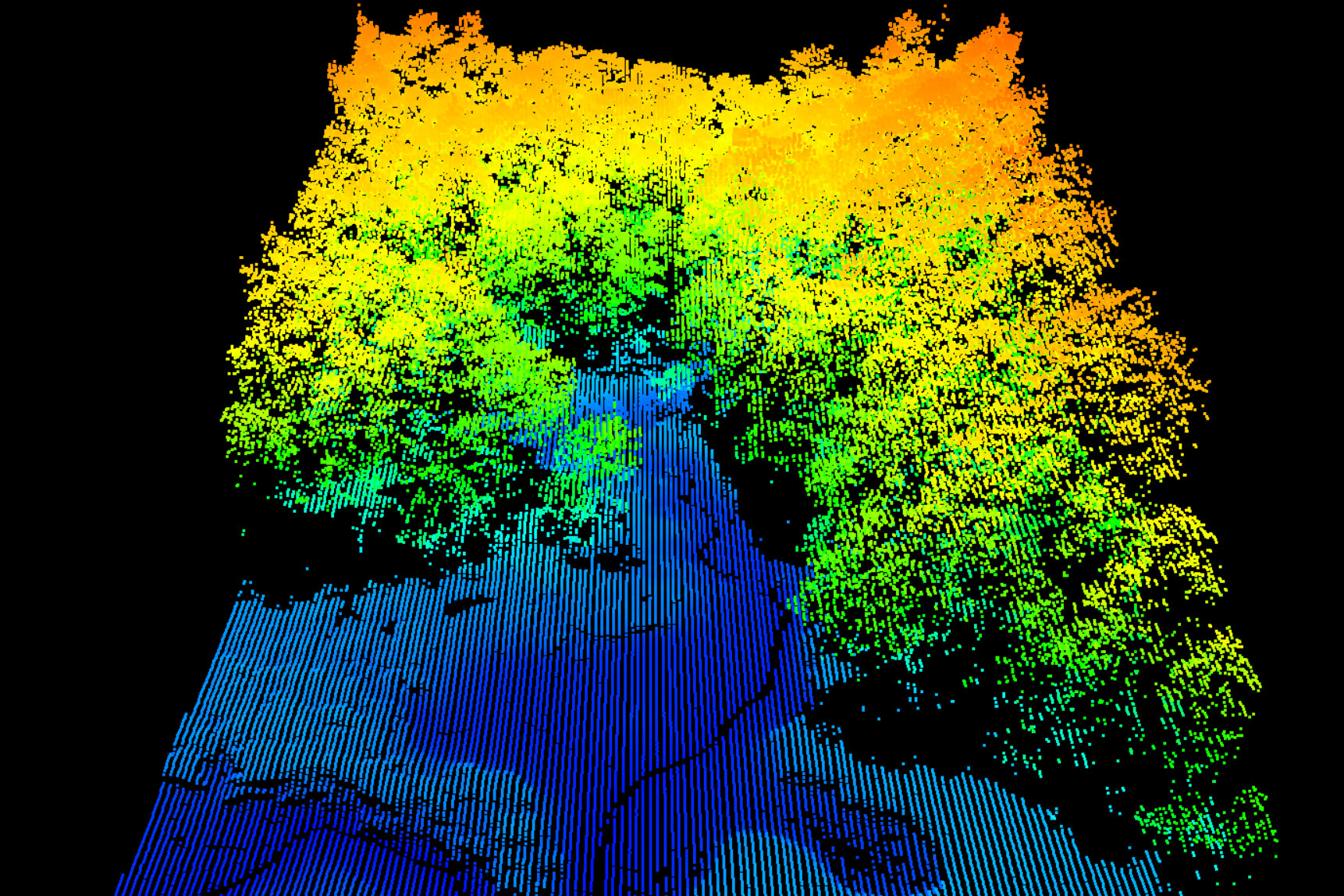

Historically, it’s been an entirely manual task to measure trees for forestation-based carbon offsets. You have to send people into the forest to take sample plots, count the trees, measure them with tape, and validate how much carbon is actually in that forest. It’s expensive, slow, and prone to error. Plus, a company would do this only once every five years or so to be eligible for certification, so the information is out of date nearly immediately. The manual verification certification process can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars because of all the human-power required.

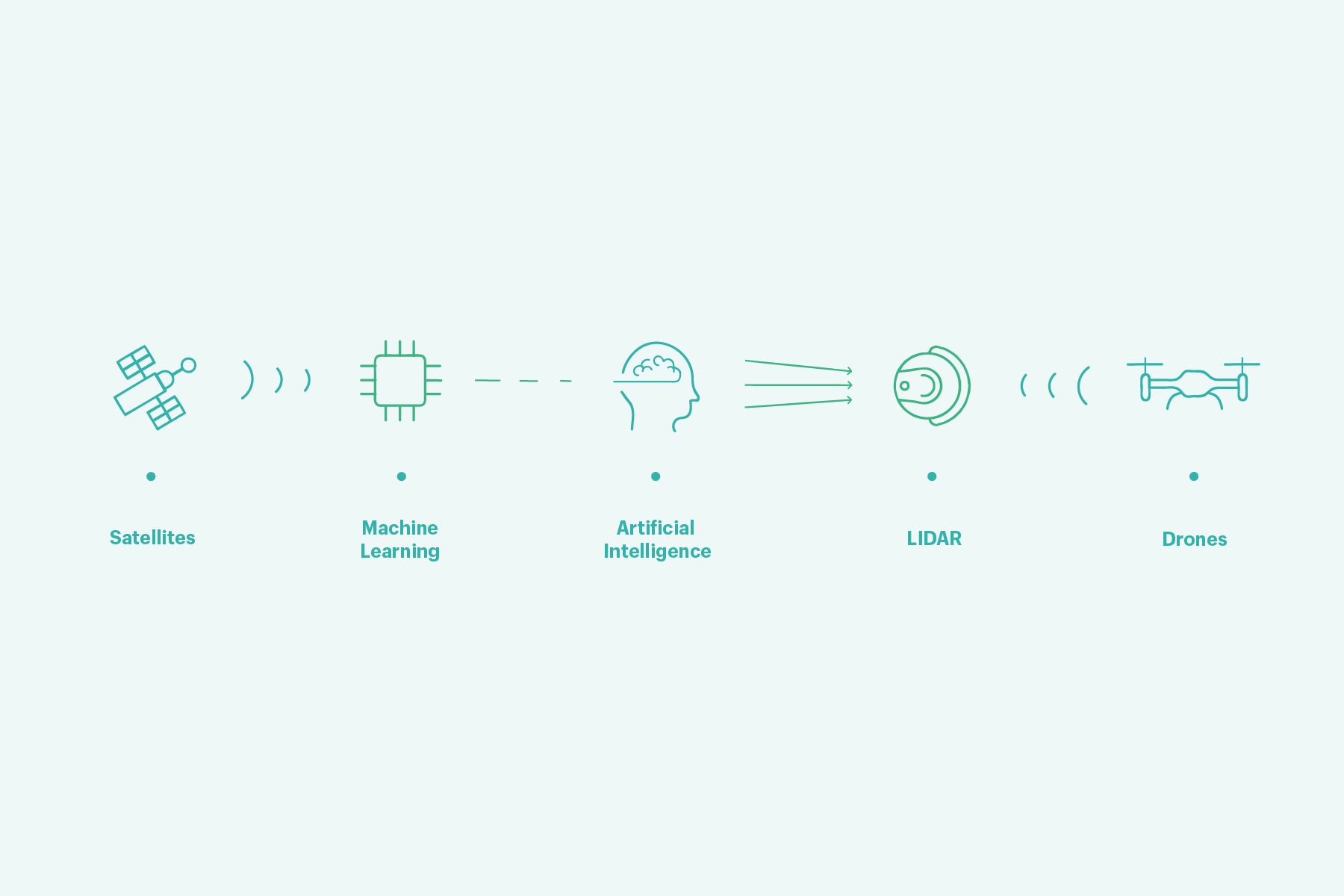

Meanwhile, today we have a plethora of satellites taking near constant photos of the earth below. We have machine learning and artificial intelligence that can help process all of these images, developing algorithms to make predictions about the amount of carbon in a given area. There are also technologies like light detection and ranging (LIDAR), which three-dimensionally scans an environment by shooting laser beams to measure distances. And don’t forget about drones that can now fly super long distances.

“Our goal was to bring together all of these technologies that the tech world had advanced and use them in the service of making this industry more efficient, more transparent, and more credible,” Diego says.

And that is our catnip: passionate entrepreneurs using cutting-edge technologies in novel ways to solve massive problems that have never been solved before.

Instead of supporting just one forestation project, Pachama is implementing a patchwork-quilt approach, building a marketplace of various projects from around the world that people can choose from.

That is our catnip: passionate entrepreneurs using cutting-edge technologies to solve problems that have never been solved before.

“We’re building an online platform,” Diego says. “...we want to democratize the way that foresters and farmers can access companies and people who are increasingly going to start offsetting their carbon emissions. That’s the only way this is going to scale.”

Their goal is for tens of thousands of new forest protection projects to pop up all over the planet and for Pachama to be the connector.

Trees aren’t a perfect solution. They can be burned, razed, or infested by pests. There’s plenty of room for error when calculating the total number of trees in a protected area. There are even studies showing that forests are losing their ability to absorb carbon because of droughts and higher temperatures.

But there’s no denying that maintaining our existing forests and adding more trees is good for our planet. They support farmers and landowners around the world and ensure that all the creatures within them retain their home.

The anatomy of an offset

We’ve chosen two forestation projects so far with Pachama, one for our Offset app and one for Shop.

Merchants using our Offset app will be investing in the Jari Pará Forest Conservation Project in the Amazon rainforest. This project covers 496,988 hectares of tropical forest in Brazil, an area the size of the state of Delaware, protecting more than 2,400 species of flora and fauna within it.

If you make a purchase using Shop Pay, Comfy Morning will offset the shipment of your package via the Brazil Nut Concession Forest Conservation Project, which protects more than 291,566 hectares of tropical forest in Peru and will prevent 14.5 million tons of CO2 emissions. This project is made up of 143 parcels of land operated by 377 Brazil nut farmers.

Both of these projects are Verified Carbon Standard certified projects that will be monitored by Pachama using their machine learning, satellite imaging, and remote monitoring technology. Our price per ton covers the project costs to protect the existing forest, increase the biomass through improved forest management practices, and verify the project’s progress. But let’s get more specific about where those dollars go.

At the end of the day, Pachama is a business. For every dollar Comfy Morning invests with them, 20 cents goes to Pachama for their commission, and 80 cents goes directly to their forestation projects—more specifically, the people who own the land and are protecting the trees.

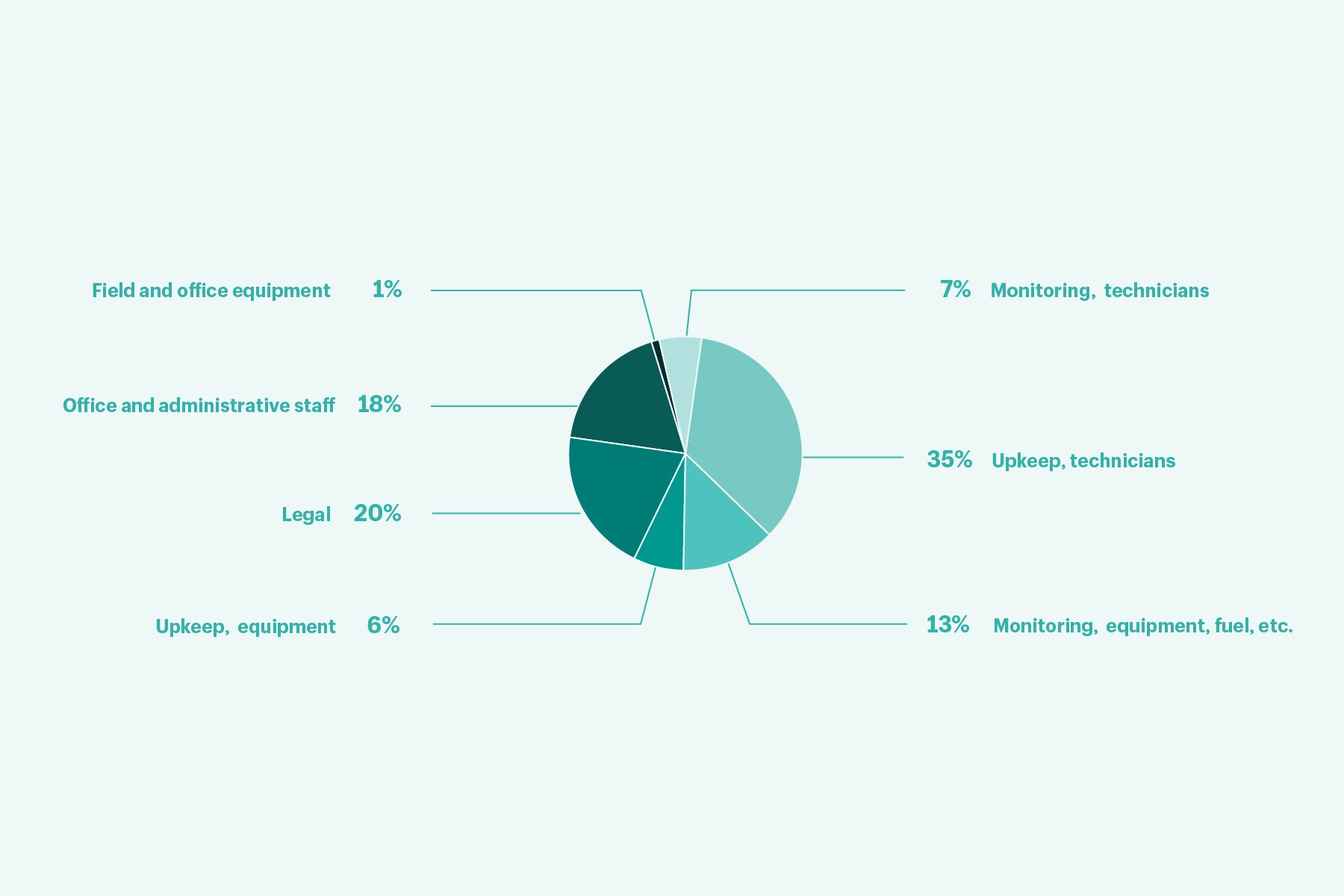

Pachama’s 20% is split between various costs, including:

- Paying for satellite imagery and data (from Planet and Maxar)

- Initial verification of the quality of projects and continuous monitoring afterward

- R&D: Pachama has a team of PhDs, data scientists, and engineers who work to refine the processes mentioned above and develop new technologies for measuring the carbon biomass of forest plots

- Creating customized impact pages

- Staffing

The remaining 80% allotted to their projects is broken down on a case-by-case basis.

As an example, here’s a breakdown of an anonymized project’s annual operating costs:

The revenue generated by a project like this one depends on the size of the project, how many credits they choose to (or are able to) sell, and the price they charge. There’s a large upfront cost to launch and verify any project, as well as substantial ongoing monitoring fees. A large proportion of the profit retained by the project developer is set aside for periodic third-party verification and auditing (which varies significantly depending on the project size and location), and the remainder is split between the project developer and the landowners.

Why protect existing forests instead of planting new trees?

The short answer is, both actions are essential, and we’re doing both. There has been a lot of global momentum around tree planting, like the Trillion Trees initiative and Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke’s commitment to planting 1,000,001 trees, but it’s incredibly important to protect old-growth forests as well. New trees take years to develop their carbon-absorbing powers; mature forests are already doing the job.

Not only this, but existing Amazon forests are home to 10% of the world’s known species (with more than 2.5 million insect species alone) and 40,000 different plants—many of which are the basis of essential pharmaceutical medicines. Preserving these ecosystems, and supporting local communities that protect them are also brilliant side effects of conserving existing trees.

Sadly, illegal timber poaching of the rainforest is leading to deforestation at a rate of three football fields per minute—we’ve already lost around 17% of the entire forest, and projects like these seek to slow and prevent this loss.

Carbon offsets are not the solution to climate change

Carbon offsets alone won’t solve the problem of global warming. Not by a long shot. We’re not saving the planet by investing in them, but we are reducing the amount of overall carbon that we’re emitting, and if a bunch more people did that too, it would make our climate goals a whole lot easier to achieve.

There are one billion hectares of land on earth where we can plant trees without impacting agriculture. This would allow for 1.2 trillion trees, which could capture more than 200 gigatons of carbon from the atmosphere, wiping out a decade of the damage we’ve already done, according to a Swiss study.

It’s not nearly enough. But it’s a start. We’ll continue to offset what we cannot eliminate, and we'll keep investing in other solutions to figure out what works best.